Phedon Papamichael, ASC plays fast and loose [with cinematic conventions] in Oliver Stone’s controversial new biopic

“This is the story of a guy who would have been happy to be the commissioner of baseball, but instead wound up as leader of the free world. Though lacking in patience, he does show a measure of charm in some of his dealings with people.” So states cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, ASC, in describing W.’s titular character. Like most of his projects, director Oliver Stone’s biopic of outgoing President George W. Bush has generated plenty of controversy in the months leading to its release. (Sources said a handful of major studios passed on W., despite financing that underwrote distribution print and advertising costs.) But those expecting the nation’s 43rd President to be skewered by cinema’s reigning provocateur will be disappointed. “It’s hard not to play comedy when you have quotes from history that are funnier than anything a writer could make up,” Papamichael allows. “But that isn’t the picture’s intent; furthermore, it’d be too easy and Oliver wants to accomplish more than that.”Early reports indicate Stone’s film is loosely structured like an epic Shakespearean tale: W.’s early years as a hell-raising party-boy, followed by his subsequent religious conversion and eventual rise to the national stage and the Presidency, the latter of which continues to provide the White House press corps with fodder. Just back from a scout in the Peloponnesian Mountains for an upcoming directorial effort, Papamichael says there’s some “entertainment value” in seeing how Bush’s decision [to invade Iraq] gets as much thought as when he decides he wants to barbecue. But he adds that biopics, by nature, engender sympathy for their subjects. “Bush’s problems and mistakes are public knowledge,” says Papamichael. “But there’s another insight here that humanizes him to a degree.”

The Campaign’s Early Days

The cinematographer’s relationship with Stone dates back to the Stone-produced Wild Palms miniseries, just after Papamichael finished a run of films with low-budget producer Roger Corman. The DP says he also interviewed with Stone for On Any Given Sunday, calling the experience [tongue firmly in cheek] a “fun” process. “Oliver likes to rattle your cage to see if you can hold up to the pressure,” reflects Papamichael. “During my Sunday interview, he said he hated all my pictures except for Mousehunt! For this interview, he was strangely complimentary of my recent work.”

W.’s modest $30 million budget (debt financed by independent QED International) featured thirty interior and exterior locations [around Shreveport, Louisiana], plus stage work, all in just 46 days. The camera team benefited from having a pre-rigging crew on the shoot, which only required sets to be built for a few key rooms, i.e., the Oval Office and the Vice-President’s office. “I treated the stage work as much like the location interiors as possible,” Papamichael says, “maintaining the same exposure relationships. I always motivate using natural type sources through windows. I like to blow out the backdrops and cycs, because the windows on a real location usually read hot.”

Format-wise, he relied on 3-perf super-35mm, using a pair of Panavision Millennium XLs (one for A-camera, one for SteadiCam), and a Platinum as the third body. The DP carried a full set of Panavision Primos, plus an 11:1 zoom and two 4:1 zooms. Papamichael opted for Fuji’s Eterna 250 stock, which he says has wide latitude. “I used the Fuji 250 for day exteriors on 3:10 From Yuma, despite it being a tungsten stock, just because I wanted to maintain the textures,” he explains. “If I really had to, I’d go to Fuji’s 500 stock for the few extreme conditions.” He adds that his W. camera team used a range of Chapman/Leonard products, including a twin-axis hydrascope remote head, to help make their shots.

Political Makeover

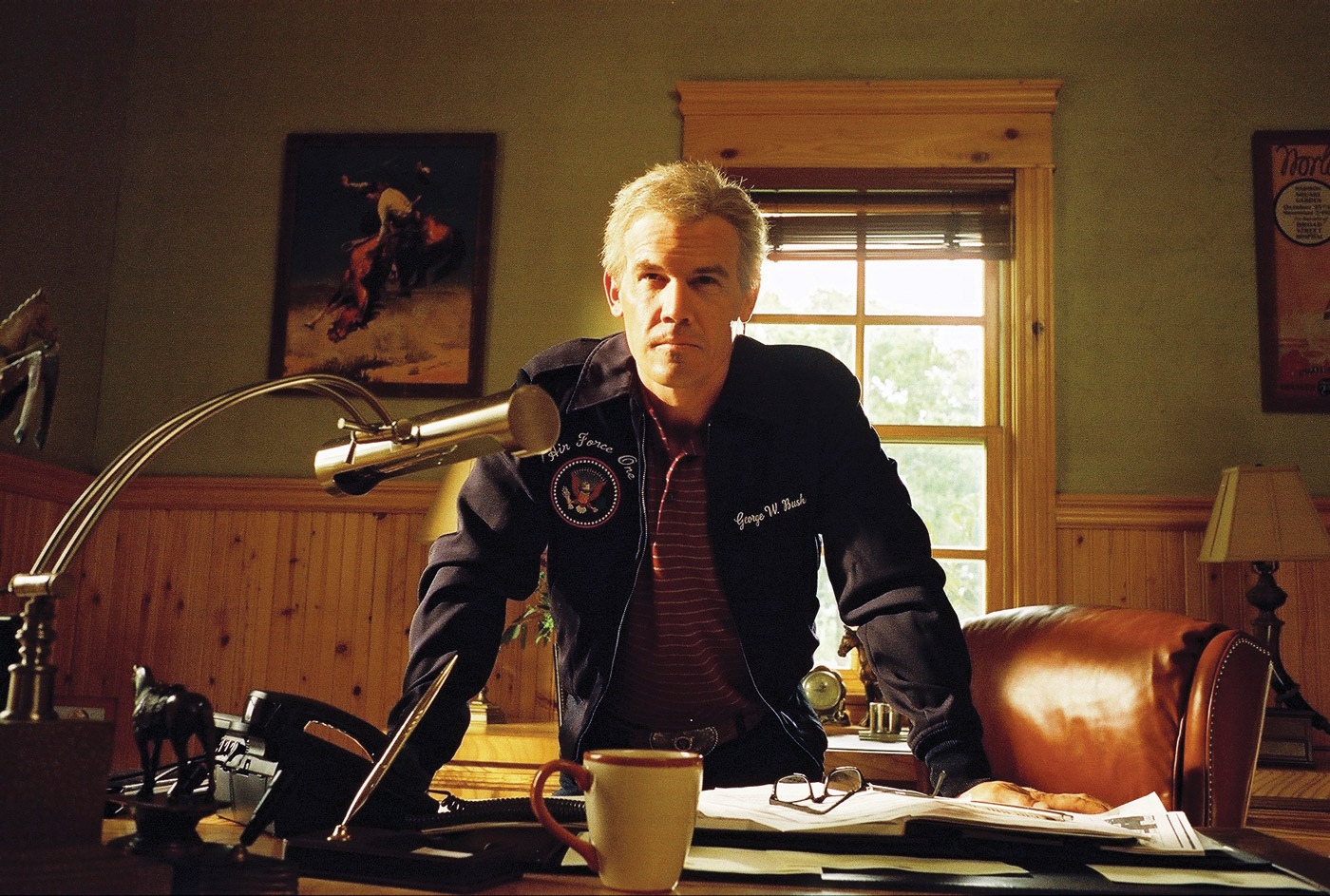

W. jumps back and forth in time, but it was shot chronologically, which helped lead actor Josh Brolin’s physical transformation. Brolin starts off with his natural hairline, and by the time W. runs for governor, his head was shaved to accommodate the first of four wigs. Extensive makeup tests were conducted during prep, but Brolin only wound up with a small application to his nose, to increase his resemblance to Bush in mid-life. “Limiting the prosthetics afforded Josh the greatest freedom of expression,” Papamichael describes. “He’s a loose, improvisational actor, so we didn’t work to specific marks. With only generalized blocking, depth of field for focus could have been an issue, but in most instances, we were able to keep a T2.8/4 split.”

A decision was made to vary the multiple eras in the story with subtle visual cues. “We made a chart breaking down each period, but nothing a viewer would be conscious of when viewing the picture,” adds Papamichael. Among these applications were a series of filtrations that helped capture Bush in age-appropriate light. Mitchell B and C diffusion were used for wide and tight views of W. as a young man. “It isn’t as popular these days,” first AC Jose Sanchez allows, “but in the past it was used to make ladies look better, and it helped Josh play younger.” For Bush’s ‘middle years’ Papamichael went with regular Tiffen Pro-Mist, ranging from one-eighth to one-quarter, which let things bloom a little, and helped the idea that the character was becoming spiritually awakened. After W. becomes president, the DP opted for one-eighth of Black Pro-Mist for his lens filtration.

Another method used to convey the 43rd president’s interior tensions involved varying the shutter. “The early years look a bit starker,” Papamichael reports, “so we went with 90-degree and 120-degree shutters to convey his restlessness and tension, and help emphasize the conflict with his dad [James Cromwell.] We left the shutter effects out of the middle period, but then reemployed them when he is a president in crisis. The film becomes more monochromatic, and I let walls fall off into darkness. We also played some wider angles in the Situation Room, where we didn’t want to spend time covering everybody in singles. The room is like the War Room from Dr. Strangelove, so we built a light panel over the conference table to evoke the [Ken Adam-designed] overhead light ring in that film. “

A Maverick In The House

Allowing for the short schedule, Stone opted for many of shots to be done in just a few takes, although each had its own quality. “A-camera and SteadiCam operator Gary L. Camp would be allowed a more traditional way of framing that would usually be take one,” says Papamichael. “Oliver asked me to use Danny Hiele to operate B-camera, and Danny’s take would have a different style. He’s a DP with a music video history. Oliver likes to let accidents play, so even if Danny did some aggressive stuff, like going right in to minimum focus or a bit beyond, Oliver kept telling me to let him go. He’d say, ‘If we can only use twenty percent of the shot, that’s fine, it’s another option.’ It illustrates how open Oliver is, and the challenge it presents for camera people, myself included. I always want to meet and work with directors who will take me places I wouldn’t go on my own. “

That sentiment is an apt description for some of W.’s extreme shallow-focus shots, where only one area is in sharp focus to convey a distorted perspective. The visual was achieved with the Lensbabies system, pioneered for still camera use and converted to film via Panavision-made adapters. Papamichael characterizes Lensbabies as a technical variant of the Arri lens used by Janusz Kaminski on The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, which allowed for manipulation of the focal plane. “But while this is like a swing and tilt,” he notes, “you don’t rotate it into position. You can pull to one side to get a particular plane into focus. The operator is the only one who can see what is happening focus-wise.” The technique was used for a number of subjective shots as well as close-ups. It was applied for W.’s POV when he was drunk, and later when he is trying to listen to preachers, suggesting his drifting perception and limited awareness. To emphasize moments when Bush is overwhelmed or confused, close-ups were used, focusing only on his mouth or one eye.

A Wild, Wild Ride

Even with extensive pre-visualization by visual effects supervisor John Scheele and Stone’s own pre-planning, W. was still a process of discovery, even beyond the use of Danny Hiele’s experimental framing. Papamichael says that Stone is the first to say, ‘if I get bored with a shot, I won’t use it.’ “Oliver will ask for a new lens on take 2, or want to move the setup,” the DP adds, “so my lighting had to allow for these spontaneous adjustments without killing any momentum due to re-rigging. I’ve got forty pictures of experience and it required every trick to help him meet his goals.”

Such spontaneity can prove painful in more ways than one, as the cinematographer experienced firsthand. After learning to fly, W. celebrates by soloing in a Cessna in a sequence that might be described as Mr. Bush’s Wild Ride. “Usually that’s done with green screen,’” observes Papamichael. “But Oliver got hold of a clown pilot from an air show and had us up there for real. While Josh pretended to fly, I was completely nauseous from all the maneuvering. Unorthodox as it may sound, Oliver’s approach was the right one, because it gave the scene a crazy energy that makes it work.”

Partisan politics aside, a claim can be made that the same “cowboy up” daring that led to the improbable rise of George W. Bush as the world’s most powerful man, found a kindred spirit in Stone’s free-form cinematic exploration. Certainly those on W.’s camera team will never forget the shoot, which Jose Sanchez calls “one of the finest experiences” of his career, in part due to a pair of ambitious all-in-one shots. “As planned,” Sanchez explains, “they were to be the opening and final scenes of the picture, done on location as day and night shoots, and were technically very tough. But we didn’t get shortchanged on time; we got whatever we needed for prep. As a result, we didn’t have to work long hours, but it also meant when you say you’re ready, you had better be really ready.”

The scenes, which are visual and thematic bookends, offered a true measure of Sanchez’s skills. The first shot opens the film, filling the frame with an extreme close-up of Josh Brolin’s eyes and, with the camera, mounted on a jib arm and circular track, rapidly pulls out to reveal him standing in the center of an empty baseball stadium in bright daylight, the roar of an imaginary crowd deafening around him. The move goes from minimal focus to an extreme wide angle (180 degrees of rotation) in a matter of moments. The final shot of the film echoes the opening, only in reverse, and at night. Back in the baseball stadium, Bush runs back to catch a fly ball and stops, staring up at the big open sky. The Technocrane move starts equally wide and swiftly pushes all the way in to a big-screen close-up of Brolin’s eyes, as he stands, lost, waiting for the ball to come down.

Papamichael acknowledges the two moves presented obvious focus problems for Sanchez, but adds, that, more than any one sequence, the biggest challenge over the course of the film was simply keeping up with Oliver Stone. “He’s the hardest working director I’ve ever collaborated with,” Papamichael concludes. “You’re pushed to the max on his pictures, and when you drive home at the end of the day, you know you’ve earned your salary.” Summing up his thoughts on the film, the cinematographer states, “People who like George W. Bush will probably like the movie’s portrayal; in fact, some people might even like him more after seeing the movie.” Speaking to the issue of the film’s authenticity, Papamichael is, well, politically correct (unlike W.’s subject matter!). “Honestly, I can only hazard informed guesses,” he grins. “Whether some of the speculative scenes are word-accurate or not to history … well, who can say what really goes on behind closed doors?”

Come this election season audiences may finally get to find out.

by Kevin H. Martin