The cores of our craft: creativity, collaboration, and inspiration

Well the future is here, finally. And it’s not looking good for film, I have to admit. Recent developments by all the manufacturers means that most of the limitations that previously existed in digital photography have gone away and film is starting to look like yesterday’s technology. Some DPs are being encouraged to remove things shot on film from their reels because it looks “old fashioned.”

What’s brought about this change in thinking? Mostly a lot of small advances, mainly in relation to highlight clipping – always the signature of digital but now a thing of the past. Advances in sensors and dynamic range (with HDR looming) have enabled this to come about. Both Alexa and RED reportedly have a dynamic range “greater than film.” Of course, what is on the tin is not necessarily in the result, but I am seeing work that indicates astonishing range of tones, colors and other hallmarks of modern photography.

Where is it all going? Plainly, for the next generation, learning film might be a thing of the past, or just a teaching tool. A number of teachers have written online that they want to continue teaching film for as long as possible: not for the result, but for the process. Pre-visualization was an essential tool of film, which is also an important part of learning to fashion images. This would seem to make sense if cinematographers are going to continue to have a job: directors can, after all, just hire a technician to take care of the camera and “workflow” and then do their own lighting, as many do.

So what then will be the role of a cinematographer in 2020?

A pessimist might argue that since the control is slipping from on-set to post production, it is more likely the director and the digital colorist will control the final image. I have also noticed, of late, an increasing number of announced features on IMDB that list everyone except the director of photography. I can only conclude that these are films where the director has assumed the cinematographer’s role, since gaffers, operators, etc. are on the list. Much of these changes have come about through the demystification of the image making process. No longer do you need to understand the zone system, ASA and film stocks when you can see the image on a monitor and, if you like it, shoot it! (Assuming someone has lined it up properly.) As others have pointed out, the new cameras are like different film stocks – choose a camera and you’ve chosen your “stock.”

And truth be told, most of the hundred of stock tests I have done were of not much interest to the directors I worked with. They would participate in the process – even express some enthusiasm for the differences, if they could see them. But in the end, they almost always went for my preference. Why? Because they trusted me to do my job. If we did a casting test and I offered comments about an actor, they might agree or disagree, but in the end they make their own decisions, because casting is the director’s realm. And whilst the cinematographer is part of the camera team, that “team” has a leader and the leader needs to show what he or she is made of to have some influence.

So will cinematographers still have a job in 2020?

The answer is definitely affirmative, providing we continue to show strong leadership in our collaboration with producers and directors. We obviously have to know all about cameras, the post-process, and lighting because without the knowledge of what is going on producers and directors will think: Why do we need a DP? They do not have the time or the technical expertise to fully know how it all works, but they will be keen to take a position and influence you down the cheapest path. The cinematographer’s job is always to do it right. In the end, we are always the best option because it’s the most efficient way to make a great looking picture, where everyone makes money.

Did you know that on a typical picture with a budget of more than $10 million (BPS), the camera budget (whether film or digital) represents, at the most, six to eight percent? So, when a production manager starts splitting hairs about this or that camera costing less, the overall affect on the budget is actually fractions of one percent, all for choices that will impact the entire look of the film. In these situations the director of photography has to be unified with the director, so the choices are the truly best ones for the film. When Martin Scorsese chose Robert Richardson (ASC) to shoot his most recent picture (produced in 3D), Huge Cabret, it was not because Richardson knows everything about the 3D format, which I am sure he doesn’t. Richardson was chosen because he’s worked with the director before, and because he’s a brilliant cinematographer, both in terms of lighting and framing as well as, and most importantly, creative collaboration.

Collaboration, by the way, is a very different thing, from agreement, which is never going to be very interesting for a director. Creative collaboration is more like a debate and might sometimes get rowdy or adversarial, but if it leads to doing it the right way then those altercations will be quickly forgotten. The brightest minds in education are focusing on the fact that creativity is probably the single most important quality to impart to the next generation because one thing is for sure: we have no real clue what the world will look like in 2020. So in this little corner of the world – moviemaking – creativity will be the prime quality the next generation of cinematographers can continue to offer.

Here’s a good example: a director I once worked with came in every morning at 7:30, looked at the set, and announced he wanted to start with a high wide shot in the corner. (He usually would mumble this whilst cursing the late arrival of his coffee.) I would say something polite knowing it was better to fight the good fight after the actors had come in for rehearsal. Once the scene was nailed down, a series of shots would present themselves to me and I would discuss these with the now wide-awake director! We never did shoot his high wide-shot (despite the fact that he mentioned it every morning) because there was always a more appropriate shot that came from the scene (not from laziness). A director who elects not to have a director of photography on set might, like Stanley Kubrick, actually know what he is doing with the camera and get a good result. But a director like Stanley Kubrick might also benefit from bouncing his ideas off the likes of a John Alcott (BSC). The Coen brothers storyboard most of their work, so why do they continue to use Roger Deakins (ASC, BSC) when they could have a gaffer and an operator do the job? Need that question even be asked?

If cinematographers are going to be out there in the world of filmmaking (filmmaking being a very retro term in 2020!), we need to continue to provide the same essential ingredients that we have been doing for more than a century: creativity, collaboration inspiration. It’s fine to talk technology amongst ourselves, and our equipment suppliers, but don’t bring that to the director/producer meeting. By that point, you should know what you are recommending and why. And what happens if the director fires a technical question about some arcane bit of workflow modernism you’ve yet to study up on? Simply reply how interesting it will be to figure that out together during pre-production and make sure (if you get the job!) that you are fully informed when it next comes up. Technology, after all, is changing on a daily basis. I recently heard about an iPhone app that removes the rolling shutter effect! How fabulous is that?

Clearly our biggest single challenge as cinematographers is to remain invaluable in the moviemaking process. There’s lots of other jobs out there that use movie cameras (and iPhones) but the one I love, the one I have been doing for 30 years, is being a cinematographer. So all of you who are doing that job now, or would like to do it in the future: make sure your opinion is heard, lest it may never be required. The best analogy might be a patient (aka the director), who turns up to the doctor (aka the DP), with an armful of Internet printouts. The doctor listens, nods and agrees with the patient, and then prescribes what he or she considers appropriate based on years of experience and training. Not many patients get rid of their doctors (although some do!) and so it will be with our profession.

We are at a crossroads: time to stand up and be counted.

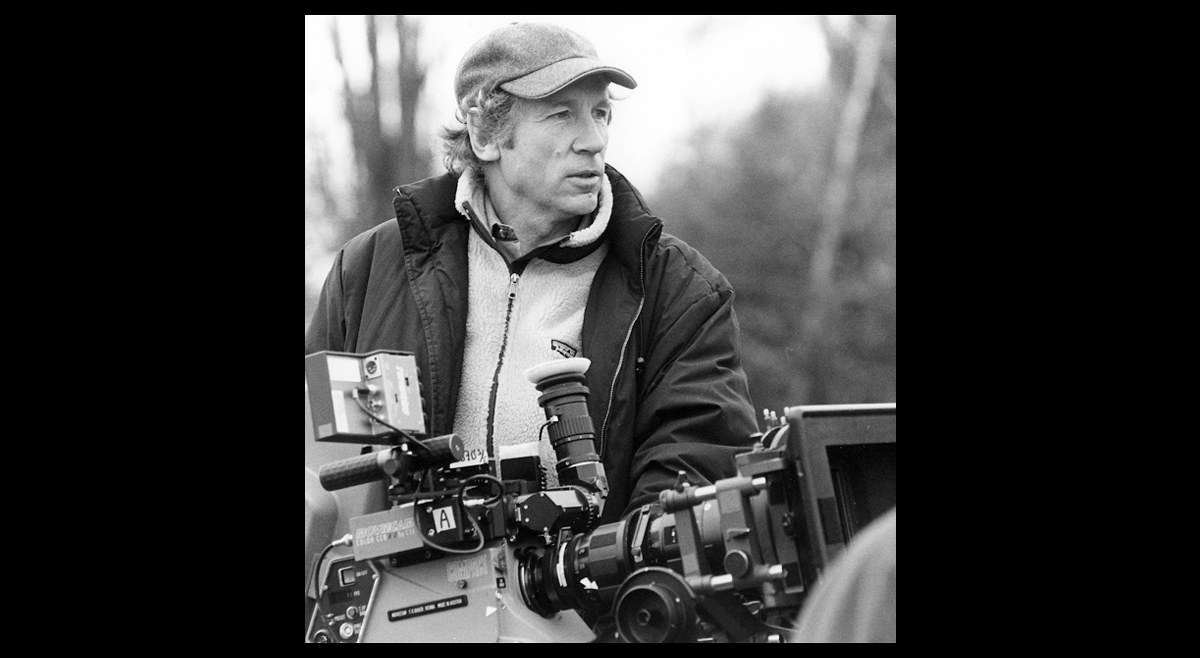

U.K.-based Oliver Stapleton, BSC, has photographed a broad spectrum of acclaimed films, including five collaborations with director Lasse Hallström starting with The Cider House Rules in 1999. He has teamed with filmmaker Stephen Frears eight times, beginning with the seminal film My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), and with director Michael Hoffman on four occasions, including the Oscar-winning Restoration (1995). Stapelton began his career shooting documentaries and music videos, winning an MTV Video Award for Best Cinematography for Take Me On, from the band A-Ha. The Water Horse (2007) marked his first VFX outing, teaming with New Zealand-based Weta Studios, fresh off the Lord of the Rings series and King Kong. In the last two years Stapelton has shot the mega-hit The Proposal, as well as Guillermo Del Toro’s upcoming horror film Don’t be Afraid of the Dark. Stapelton maintains a website, www.cineman.co.uk, primarily aimed at young people thinking of joining the film and television industry.

By Oliver Stapelton, BSC. Photos courtesy of Oliver Stapelton.