Owen Roizman, ASC and Tobias Schliesser, ASC get on track for The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3, then and now

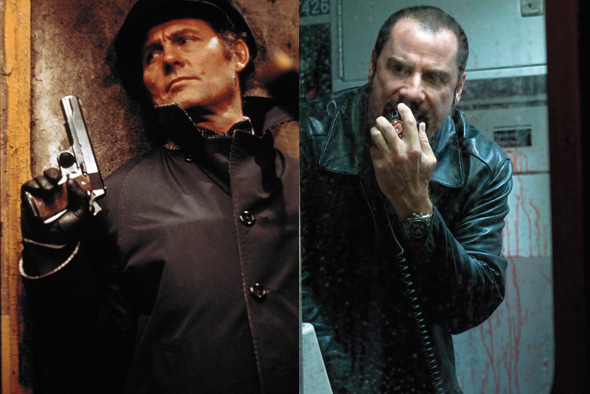

Owen Roizman, ASC shot The Taking of Pelham One Two Three in 1974. The independent feature primarily takes place in the New York City subway on a train, station platforms and tunnels. Four tough guys code named blue, green, grey and brown highjack a train and demand a million dollar ransom. The lives of the terrified passengers are at stake. Walter Matthau plays a veteran transit cop who negotiates with both the highjackers and City Hall. Thirty-five years later Tobias Schliessler, ASC shot a contemporary version of that memorable film with a few new twists in the plot. John Travolta is cast as one of the hijackers and Denzel Washington plays the negotiator. Bob Fisher sat down with both cinematographers as the pair shared and compared experiences of shooting the same story decades apart, with different technologies and directors at the helm.

SCHLIESSLER: Owen, you had about a half dozen credits before you shot this film, including The French Connection and The Exorcist, which are now considered classics. This was your first collaboration with (director) Joe Sargent.

ROIZMAN: I had worked with (producer) Edgar Scherick on The Heartbreak Kid. I hadn’t worked with Joe before, but I saw The Marcus-Nelson Murders on television, and was very impressed with the look and the feelings that it evoked. I was excited to work with him. I also thought the script had interesting characters and a cool plot. I was in familiar territory. I had traveled by subway a lot when I lived in Brooklyn. I had also shot a sequence for The French Connection in a shut down subway station.

SCHLIESSLER: Why did you suggest shooting The Taking of Pelham One Two Three in anamorphic format? ROIZMAN: Before I came onboard, they had planned to shoot it in 1.85:1 format. I went to the station where we going to shoot, rode trains and walked around the platforms. I decided that the anamorphic format would allow us to get more information into shots and more interesting close-ups. I noticed that the subway cars were almost perfect 2.4:1 dimensions. I also began thinking about how we were going to create lighting that looked and felt natural on subway cars. We had scenes with many people on the train doing different things with nothing happening at the tops and bottoms of frames. I instinctively felt anamorphic framing was right for this story.

At first, Joe and Edgar said no. In fact, they sounded incredulous. I explained why I thought it would be more interesting, and suggested that I shoot a couple of tests in anamorphic and 1.85:1 simultaneously with trains coming in and going out of a station, and with people on the train. I had a small crew and shot with available light. It was no contest when we screened the footage the next day! Everyone agreed that the anamorphic format was right for this film.

SCHLIESSLER: How did you manage to shoot in relatively dark places with comparatively slow lenses and a 100-speed film?

ROIZMAN: I remember thinking that a 100-speed film was fast, because when I first started in the business the film speed was 25! A 100-speed film was a huge luxury for me. But to answer your question, I had Movie Lab pre-flash the negative at 20 percent with an optical printer. That allowed me to record details in the shadows with very little light in the tunnel scenes. I had never done it before, but Vilmos Zsigmond (ASC) and other cinematographers were post-flashing film after they shot it. That was more risky, because if something went wrong, you lost a day’s work. There was an extra expense for pre-flashing, but Joe and Edgar were on my side. I also replaced bulbs in the tunnel with 500-watt photoflood lights that were so bright that I was a little worried about streaking the lenses. We sprayed all the bulbs with brown Streaks ‘N Tips to kill any hot spots.

Now, for this new version, had you ever worked with Tony Scott before, and why and how was the decision made to shoot in Super 35 format with D.I. timing?

SCHLIESSLER: I had worked with Tony on a number of commercials. He initially considered using digital cameras. We shot a test with the popular digital cameras next to a film camera and timed the images in D.I. It was clear that film was superior in the flexibility that it gave us to shoot in challenging lighting situations. Tony likes working with Primo zoom lenses, which are faster than anamorphic zooms, so we shot the film in Super 35 format and timed it in D.I. I was mainly shooting with (Kodak Vision3) 5219 (500T). That film has amazing latitude. It sees details in the brightest highlights and darkest shadows the way the human eye does. Did you find it challenging to cover scenes on the trains, platform and in tunnels?

ROIZMAN: We mainly shot with a single camera and occasionally with two. There were no storyboards. Every morning we went through the pages of the script we were going to shoot that day. Joe was by the camera like most directors were in those days. He thinks very fast on his feet. Joe would say this is what we are going to do. He blocked shots with the actors and told me how he wanted to use the camera.

SCHLIESSLER: Was the camera mainly on a dolly?

ROIZMAN: Yes, and it was rarely ever still. We followed the actors and did tilts and pans, mainly shooting in available light with a little modeling whenever it seemed to call for it. We had the advantage of seeing film dailies. The director, producer, operator and assistant were usually there. How many cameras did you use?

SCHLIESSLER: Tony wanted to shoot with four cameras, so we could cover scenes from different angles, including close-ups at the same time. There was usually one camera on each side of a 360-degree angle. All the spaces were pretty small. The production designer helped me immensely by designing practical lighting into sets. We had fluorescent top light inside the train, which I enhanced with matching Kino Flos for the actors’ close-ups. We tried to bring the top keylight as close as possible to the frame to create a fast fall off in exposure. I let the top of the frame go one-and-a-half stops overexposed, which looks and feels right for the intensity of the story.

ROIZMAN: I worked closely with the production designer (Gene Rudolf) to lay out the lighting scheme for the control room set. It was the only set that we had. We used decorative fluorescent fixtures with standard cool white bulbs. He asked how far apart and how low I wanted them. I told him that I wanted to have some fall off between them, so the lighting wouldn’t be flat. We shot some tests and agreed that was the way to go. That was our basic lighting. I also used a white card to reflect a bit of light into shadow areas whenever I felt that we needed it.

SCHLIESSLER: Tony got up at 3 or 4 a.m. every day and drew storyboards for every scene. We had a meeting at call time, where Tony gave everyone copies of his storyboards and went through that day’s work. Tony was in a video village with four monitors and was speaking through earphones to the operators and first assistants. It was like he was directing a ballet. The lab was Technicolor and we got HD dailies from Company 3 in New York. I went there every night and looked at the actual negative on the scanner to make sure that my exposures were good and consistent. There were times when I had to compromise, because we were shooting with four cameras from different angles. I would tell myself, if necessary, we would fix things in the D.I. with Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3, but I always tried hard to get the best negative possible in-camera. Some of the more intense moments were shot and transferred at six frames per second during the D.I. to get a strobing effect.

ROIZMAN: That sounds like a more visually interesting movie than what we did.

SCHLIESSLER: Well, we had the advantage of many newer technologies. But, I think I would actually disagree: You were able to shoot a breathtaking movie that made audiences feel like they were on the train as it was happening with much fewer resources.

By Bob Fisher