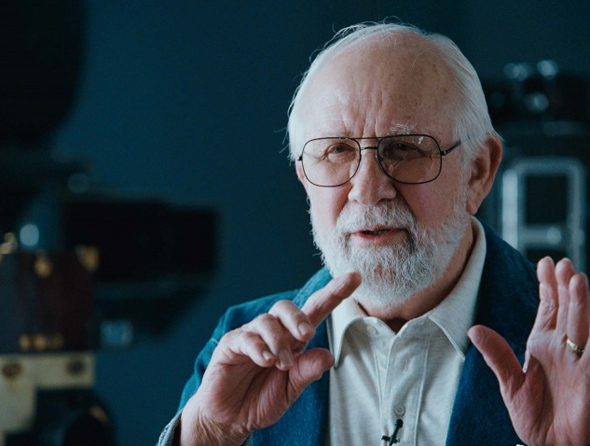

William A. Fraker, ASC, BSC recently passed on at the age of 86, following a long and courageous battle with cancer. Here Bob Fisher lovingly remembers his longtime friend and colleague

The Houston Film Festival had a tribute to the man everyone called “Billy” some three to four years ago. Billy had asked me to fly to Texas with him and moderate a post-screening Q & A with the audience. When the festival director asked Billy what film he wanted them to show, he chose Rosemary’s Baby.

I have an indelible memory of that discussion with Billy after the lights came back on. The theater was filled with 300 to 400 filmmakers, fans and students. One student said she was amazed he had shot that classic movie with a 50-speed color film before there was video assist. She asked how Billy knew what he was getting on film.

He answered her question by pointing to his eyes. Then, he put his right hand over his heart and advised her to learn to trust her eyes and what her heart tells her is right. Later during our discussion, I asked Billy if he could make one wish, what would it be. Without pausing, he replied that it would be making another film with Roman Polanski, who directed Rosemary’s Baby.

First Impressions

I met Billy for the first time in the late 1970s. It was a time in my life when I carried a Nikon SLR camera and took snapshots of the people I was interviewing to help illustrate articles. My film was processed and printed at a still film laboratory on the Paramount Pictures lot that was run by Bud Fraker.

Bud was Billy’s uncle and a still photographer for the studio for decades. He introduced me to Mr. Fraker … that’s how journalists addressed cinematographers during those days. But I remember at that first meeting how Bud told me to call his nephew Billy, and to put my camera on the shelf and concentrate on writing!

“Leave the picture taking to photographers,” he said.

Billy, who belonged to both the American Society of Cinematographers and the British Society of Cinematographers, was a uniquely talented human being. He compiled more than 50 narrative film credits as a cinematographer. There were Oscar® nominations for Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1978), Heaven Can Wait (1979), 1941 (1980), WarGames (1984) and Murphy’s Romance (1986). He also earned an Oscar nomination for visual effects on 1941, which were created in-camera. You only need one hand to count the number of cinematographers who have earned more than one Oscar nomination for a single film.

There are more than a few other memorable films in his body of work, including The President’s Analyst, Bullitt, The Day of the Dolphin, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, Spacecamp and The Island of Dr. Moreau. Billy also directed episodic TV shows and a few movies, including The Legend of the Lone Ranger and Monte Walsh in addition to shooting countless commercials.

The story of his life and career is like a script for a feel-good Hollywood movie. His grandmother was a teacher in Mexico when a brutal revolution brought Pancho Villa to power in 1910. Employees of the former government, including teachers, were on the “enemies list” and were targets for arrest and assassination.

Billy’s grandmother left Mazatlan on foot with two mules carrying her two children. They made a long and dangerous journey to the border, and entered California as illegal immigrants. [Fortunately this was not the Arizona of 2010!] Billy’s grandmother made a new life for herself and her children in the U.S. They lived in a cottage near the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Vermont Avenue in Hollywood. His grandmother supported her family by working as a portrait photographer in downtown Los Angeles.

Billy’s mother was 16 and his father was 18 when they met and married. His grandmother taught Billy’s father (who later became a publicity photographer for Columbia Pictures) the art and craft of photography. Billy had vivid memories of seeing portraits that his father took of Golden Era Hollywood stars like Anna May Wong, John Wayne and Barbara Stanwyck.

A Life Unfolds

Billy was only 10 years old when his father died. His mother died a year later. His grandmother opened a portrait studio in their cottage, so she could work at home and be there for Billy and his sister. Billy became her assistant while he was still a teenager.

He credits his aunt with planting the seed to become a cinematographer. His future got put on hold when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Billy joined the U.S. Navy on his 18th birthday. He served for the duration of the war as a signalman on an attack transport that carried marines to more than a few beaches. Years later, he said that was the genesis of his visual grammar for Steven Spielberg’s 1941.

After World War II, Billy worked as an assistant to Tom Kelly, a still photographer who took many portraits of Marilyn Monroe. I remember Billy telling me how he treasured those memories of hanging out at the studio and listening to Marilyn talk about her dreams of becoming a movie star.

Eventually Billy’s aunt “hounded him” into enrolling in the film and television studies program at the University of Southern California, which was affordable because the G.I. Bill of Rights paid for tuition. Almost all of the students in his class wanted to be writers or directors. He and Conrad L. Hall, ASC were the exceptions to that rule, and they became lifelong friends.

Both men credited Slavko Vorkapich, an expatriate from the pre-World War II German film industry, with guiding them on their journey to a future in cinematography. It was a long and sometimes discouraging journey that required extraordinary persistence.

Billy graduated from USC in 1950. In an interview, he noted that during that era, it was easier to break out of jail than into the International Photographers Guild!

Nevertheless, he lived in his family’s cottage and supported himself doing still photography, shooting 16 mm industrial films and filming “grab shots” for movies for $25 apiece. He would get a call saying that a director needed a shot of a crowd leaving a factory after a night shift. He would drive to the factory and grab some shots with his Eyemo camera.

It took seven years for Billy to get an opportunity to become a member of the Guild. One day his phone rang. Herb Aller, the business agent for the Guild, was on the other end of the line. He told Billy to come to the Guild immediately and to bring a $300 check (for his initiation fee) with him. Billy came right down, but he had to borrow the money!

After becoming a Guild member, his career began in earnest, starting as a camera loader at General Services Studio, where he worked on more than 300 episodes of The Lone Ranger and various other episodic series. Billy worked his way up through the ranks of the camera crew system on Here Come the Nelsons. He began as a second assistant up to the camera operator over a seven-year span.

Billy and Connie

Billy was also a camera operator for Conrad when he shot the TV series The Outer Limits, followed by the features Wild Seed, Morituri and The Professionals.

He told me that the most important lesson he learned working with Connie was to trust his instincts. I had many opportunities to interview Billy and write articles about his various films, including Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Heaven Can Wait, 1941, Murphy’s Romance and others, plus career retrospectives when he received Lifetime Achievement Awards from the ASC in 2000 and Camerimage in 2003.

I went to various festivals with him, including Camerimage. It was like travelling with a rock star. Gu Changwei, ASC was at the festival with Farewell My Concubine in 2003. I asked him through an interpreter if he was excited about his film being nominated for an Oscar® and going to Camerimage. His reply was that he was very excited because it gave him an opportunity to meet Mr. Fraker!

Billy never let his success go to his head. At the aforementioned Houston Film Festival, a student asked what was so special about working with Polanski. Billy described a scene in Rosemary’s Baby where Ruth Gordon’s character knocks on Rosemary’s apartment door and asks if she can come in and make a phone call.

Mia Farrow, who played Rosemary, let her in. She and her husband (played by John Cassavetes) offered up their guest a phone in their bedroom that she could use.

Gordon was portraying a witch calling members of her coven to tell them that she has found a victim. Billy carefully used the doorway to frame her sitting on the bed, artfully lit through a window on the set. Billy told the students that he proudly asked Polanski to look through the viewfinder and see how he set up the shot.

Then, he quoted the director as saying, “No, no Billy. Move the camera left until you can just see her feet hanging over the edge the bed.” Billy said that he thought Polanski was wrong until they watched dailies with members of the cast and crew, and everyone leaned left as if they were trying to see around the edge of the doorway.

On that night in Houston, Billy went on to explain that filmmaking is a collaborative art, which is what he loved the most about his life’s work. He taught that lesson to many students at USC, where he taught classes in-between shooting films. Billy literally used Rosemary’s Baby as a text book. They watched and discussed scenes, and then he would explain what he did and why. During the weeks before Billy died, he accepted an invitation from Stephen Lighthill, ASC to visit AFI and mentor students.

There is no simple way to sum up how William “Billy” Fraker touched the lives of literally countless numbers of people. He said it best in an interview I did with him many years ago. Billy quoted poet Robert Browning, “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what is heaven for?” He added that means, “Don’t sit on your laurels, because people who do that only have one laurel.”

Then, he laughed and laughed.

Billy went to heaven on May 31, 2010, survived by the love of his life, his wife Denise.