Phedon Papamichael, ASC takes viewers down the Hollywood road less traveled in the black and white road movie, Nebraska

The landscape last November in drought-parched Plainview, Nebraska, was severely muted. Post-harvest, the gently rolling fields running off to the horizon were straw-colored, and the town’s grain elevators and brick storefronts were all browns and grays. The town evoked memories of The Last Picture Show, its best days many decades past, wind sweeping in off the plains into the main square. A team of filmmakers, many from Hollywood, looked out of place.

But nothing in this tableau was unfamiliar to director Alexander Payne, who grew up in Omaha and makes capturing places like his hometown a cornerstone of an approach he describes as several parts “documentary.”

“Alexander has a real connection with people and place, and can convey this like no other director I have ever worked with,” key grip Ray Garcia explains. “Although the scenes are scripted and worked out with his actors, the many unique faces he includes are people who live in the town. He spends a lot of time observing his locations prior to shooting. So if his pictures feel like we are observing reality, it’s because of this.”

A big part of Payne’s verisimilitude is cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, ASC, who shot the director’s last two (Oscar-winning) films, The Descendants and Sideways. Those projects revealed aspects of Hawaii and the central coast of California, respectively, that had not been seen much in Hollywood movies. Payne’s latest project, Nebraska, turns the cameras on another unique corner of America rarely visited in narrative films.

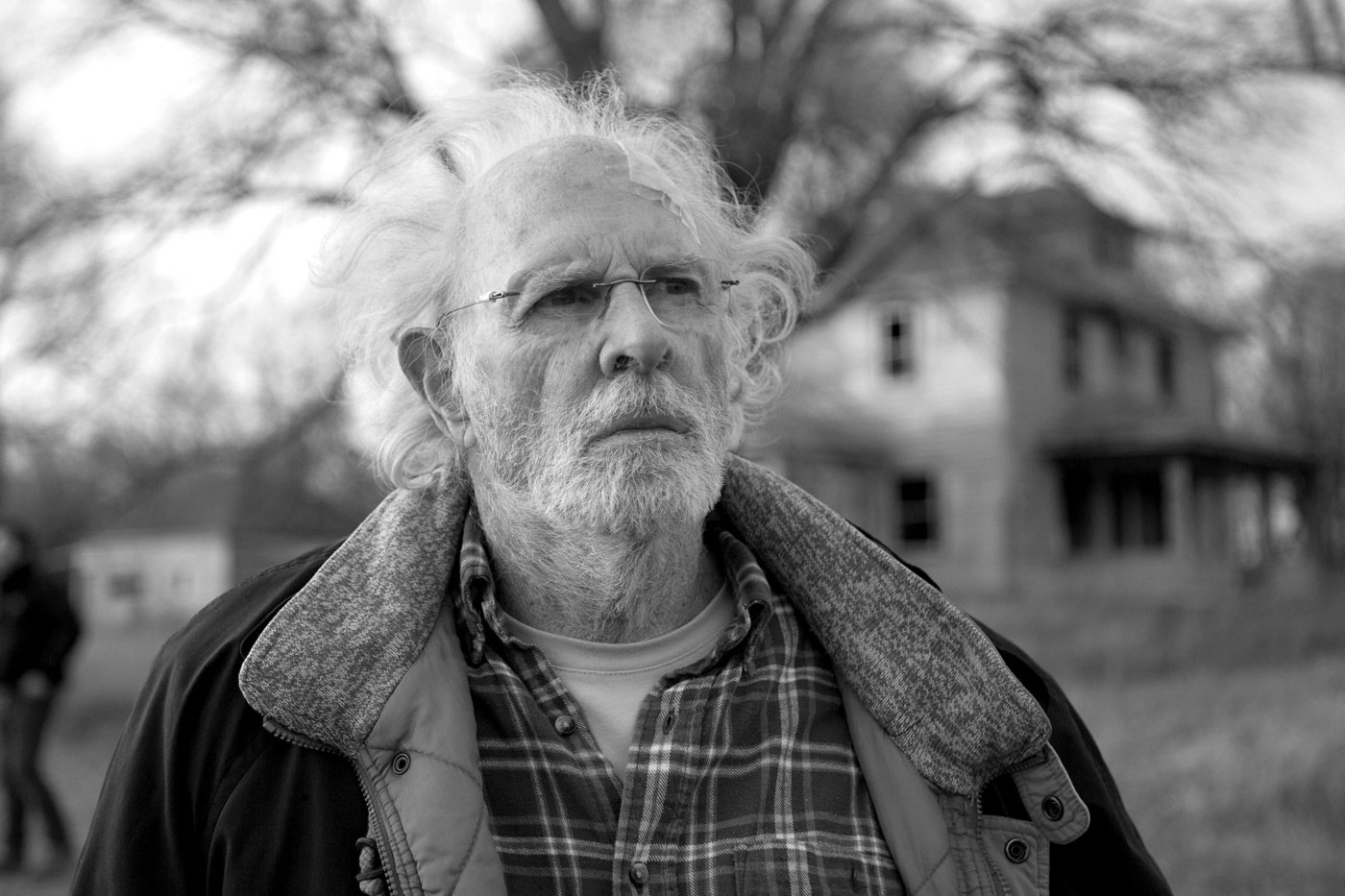

Nebraska follows a Montana man (Bruce Dern), who, approaching senility, takes a marketing flyer that says that all he has to do to claim a sweepstakes prize is to show up in Lincoln. His son (Will Forte) decides to travel with him, in part as an attempt to patch up their rocky relationship. Along the way, they stop in the old man’s hard-bitten hometown and get caught up in old grievances.

Papamichael says the choice to shoot the film in black and white – a rare animal indeed these days for a Hollywood release – was an instinctual, not intellectual, decision. “Alexander always envisioned [Nebraska] in black and white, going back to our earliest conversations, before we made Sideways,” he explains. “Although the story and the landscapes lend themselves to black and white, we never know what to say when people ask why. When I’m working on stills at home, some of them are better in monochrome. It just seems to feel right.”

It didn’t necessarily feel right to the film’s distributor, however. Although Payne is one of the rare directors who has maintained final cut (thanks to careful budgetary parameters), when Paramount realized he was serious about choosing black and white, they pulled funding. Eventually the studio came back to the table with a diminished offer of $13 million, and the project was back on track.

That’s when Papamichael set about doing tests. Kodak even offered to provide a 400 ASA black-and-white emulsion (which did not work out). But main testing compared the ARRI ALEXA, RED Epic, Eastman Double-X Negative Film 5222, which has a recommended exposure index of 250 in daylight and 200 in tungsten-balanced light, and KODAK VISION3 500T 5219 Color Negative Film with the color drained in post. The 5219 approach compared to other recent black-and-white films The Man Who Wasn’t There and Schindler’s List.

Technicolor’s Skip Kimball put the DP’s 5222 test footage through a digital intermediate, identified an ideal contrast level, and projected printed film to establish a benchmark. Knowing that the vast majority of release prints would be digital, the process was followed through to a DCI version. Then Papamichael asked Kimball to match the 5219 and ALEXA footage to the DCI. Kimball found that a grain flavor based on the old 5248 stock worked best. Much later, in the actual DI, the filmmakers were considering a heavier grain overlay, and they had Paramount send over a print of Paper Moon, which they split-screen projected, and found that the 5248 grain was matching pretty well.

Part of the decision to shoot ALEXA was based on the system’s low-light capabilities. The filmmakers shot at speeds as high as 1200 ASA, using natural light in the streets of towns like Plainview. To those who insist digital has less latitude, Papamichael notes: “The black-and-white film stocks we were considering don’t have the latitude of modern color stocks, either. And since the final image would be higher contrast, the curve wasn’t as much of a factor.

“Digital obviously has advantages in night exteriors and low-light situations,” he continues, “which makes the filming process easier. The image on the monitor includes the LUT I set. So I’m able to discuss with [Payne] where we want to go. I’m able to see my final result, almost. Those are all qualities I like. And what some people point to as drawbacks of shooting digitally aren’t a problem when you’re shooting for black and white.”

Another key aspect was using C Series anamorphic lenses from Panavision. An estimated 80 percent of the movie was done on the wider end of the range, the 40-, 45- or 55-mm focal lengths.

The C Series was introduced in the 1960s. Panavision’s lens guru Dan Sasaki retrofitted them with modern spherical elements to improve contrast and sharpness. He also re-spaced the cylinders to create a more gradual fall-off along the edges. According to 1st AC Jeff Porter, the initial plan was to use a set that Sasaki had fine-tuned for Bojan Bazelli, ASC, on The Lone Ranger. When that film’s schedule was extended, Sasaki began working on another set. The Lone Ranger wrapped a week prior to Nebraska’s start, so in the end, Porter and Papamichael got to choose the best lenses from both sets.

“Dan created an anamorphic lens with classic characteristics that could stand the test of today’s high-resolution digital cameras,” Porter shares. And Papamichael says the lenses have optical qualities that helped take the curse off the digital image. “We joked with Alexander about even adding projector flicker and destabilization,” he smiles. “Hopefully, by adding the grain and using these C-series anamorphics, we can still convey that nice black-and-white film look without going overboard.”

Shooting ALEXA required a bit of leading-edge technology. Convergent Design Gemini 4:4:4 Recorders were chosen for the ARRIRAW capture because they were compact and light. The combination of the ALEXA 4:3 sensor and anamorphic was still relatively new in the autumn of 2012.

“Convergent Design was just getting ready to release new firmware for the Gemini that would allow for 4:3 capture, but they couldn’t give us a firm date,” Porter continues. “And Arri hadn’t yet released their SUP 7 software, which allows the SxS module to become activated and record 2K ProRes as a backup. Our first break came from Stephan Ukas-Bradley of Arri, who allowed us to use the beta version of the SUP 7. Then, Convergent Design released its 4:3 capture software. The test was a bit of a disaster, but our DIT, Lonny Danler, spent the next two weeks working with Arri and Convergent Design to eliminate the bugs, and we didn’t experience a single problem during production.”

The Gemini recorded images at 2880×2160 resolution with simultaneous recording to in-camera SxS cards at 2048×1536 ProRes 4444 Log C. “I’d always have a separate BNC feed to monitor the Gemini out Log C for exposure,” Danler explains. “At my cart I would flip the live image back and forth from color to black and white [using a live LUT from Technicolor] on a 25-inch Sony OLED monitor so that gaffer Rafael Sanchez, Garcia and I could keep an eye on the frame while Phedon stayed close to the set. After the footage was ingested, I would load it into DaVinci Resolve and begin refining the live look into a dailies look that would then travel with the shuttle driver to post. We kept within the ASC-CDL specs for dailies, but in a few cases where Phedon wanted some power windows and secondary adjustments, to bring down a sky for example, I would generate some stills out of Resolve – the same software that Technicolor uses in the DI.”

The road-movie framework of the narrative required extensive car scenes, and Payne didn’t want any process shots. An ALEXA M allowed for easy placement inside vehicles and through-the-window rigs. Often the M head was on a slider in the back seat of the hero vehicle, a Subaru Outback wagon, or mounted on a leveling head on the passenger side.

“We then cabled it to the body, which we mounted inside a ventilated beverage cooler to protect it from the elements,” says Porter. “Will [Forte] even drove us through the drive-through at McDonald’s one day – try doing that with an insert car and a 25-foot process trailer!”

Payne gave Papamichael ample freedom to frame the image, “and with that big, open landscape – the roads, cornfields and skies – everything fell into place,” he says. “Bruce Dern’s face is quite fascinating with the texture, and the hair and his eyes. It was nice framing close-ups of him with a widescreen frame in the middle of nowhere. And you’re not struggling with a cacophony of colors and skin tones. It’s just a lot of fun.”

Although the filmmakers saw black and white on the set, the ALEXA/Gemini rig captured full color to provide maximum flexibility throughout the pipeline; in post, a color could be isolated and manipulated to affect the black-and-white image. Papamichael used this capability on the set, but sparingly, in part because a color deliverable was required, and he didn’t feel comfortable giving it strong colors. Asked about László Kovács’ oft-told story about the advice he got from Orson Welles about shooting Paper Moon in black and white – “Use a red filter, my boy” – Papamichael says that the color deliverable precluded that as well.

Conversations with production designer J. Dennis Washington often concerned how dark a wall should be. Papamichael sometimes said that if the wall was a certain color, he could isolate it in the DI and make it darker or lighter according to Payne’s wishes.

“Sometimes, as we were doing the DI, it got a little scary because I didn’t know what Skip was doing,” Papamichael admits. “He was playing with the colors and contrast, and manipulating the sky or skin tones. Sometimes things looked a little strange, and I couldn’t really pinpoint why. Often we would just scrap it and start over, because there are so many options when you’re playing with the color tonality to affect the black-and-white image.

“On the set, I did do certain things with color in consideration of that,” he continues. “We painted buildings red so I could make them darker or lighter by affecting the red channel. But it’s not as easy as you might think, because if there’s some sheen on the wall, that doesn’t get affected as much. And if you push it too much, it doesn’t look real.”

Gaffer Rafael Sanchez did warm up some of the colored lighting. “And if there was a kick off an asphalt road surface at night, if it had some color, it was easy to dial out,” Papamichael continues. “Sometimes in dusk situations, because it’s so blue, we could dial it down without affecting the rest of the scene. At night, we’d shoot HMI straight up behind buildings or on rooftops, which gave an atmospheric glow that was very controllable in post. We could make it really strong or almost eliminate it, as if I’d never put it there.”

A handful of Nebraska’s prints are being filmed-out to black and white print stock, and Papamichael says that these are the best versions of the movie. “When we premiered at Cannes, the DCP looked great. But once you go back to black-and-white print stock, you’re picking up additional film stock grain, and you get the film projection element coming back to you,” the DP reflects. “At that point, you’d be hard-pressed to say it was shot on a digital camera.”

Looking back at this experience, the cinematographer recalls how Payne’s emphasis [no matter the project or location] is on the people. “It’s always about the subtleties and facial expressions. Alexander doesn’t want to miss any of the nuances of the performance, so the camerawork is subtle, and nothing is wasted. The actor’s work is never covered up by a particular style – movement, rack focusing or lighting – that would distract or take away from the story. This film, like all his movies, is very precisely crafted, and I think that’s why they’re so successful. You feel the love and the labor, and the thought behind everything.”

CREW LIST > Nebraska

Director of Photography: Phedon Papamichael, ASC

Operators: Jacques Haitkin

Assistants: Jeff Porter, Martin Moody, Steve Wolpa

Digital Imaging Tech: Lonny Danler

Still Photographer: Merie Weismiller Wallace

2ND UNIT

Dir. of Photography: Radan Popovic

Assistant: Harry Zimmerman

By David Heuring. Photos by Merie W. Wallace