Dan Mindel, ASC, BSC and Pixar’s Andrew Stanton mix anamorphic film capture with ultra-slick digital VFX … for the otherworldly 3D epic John Carter

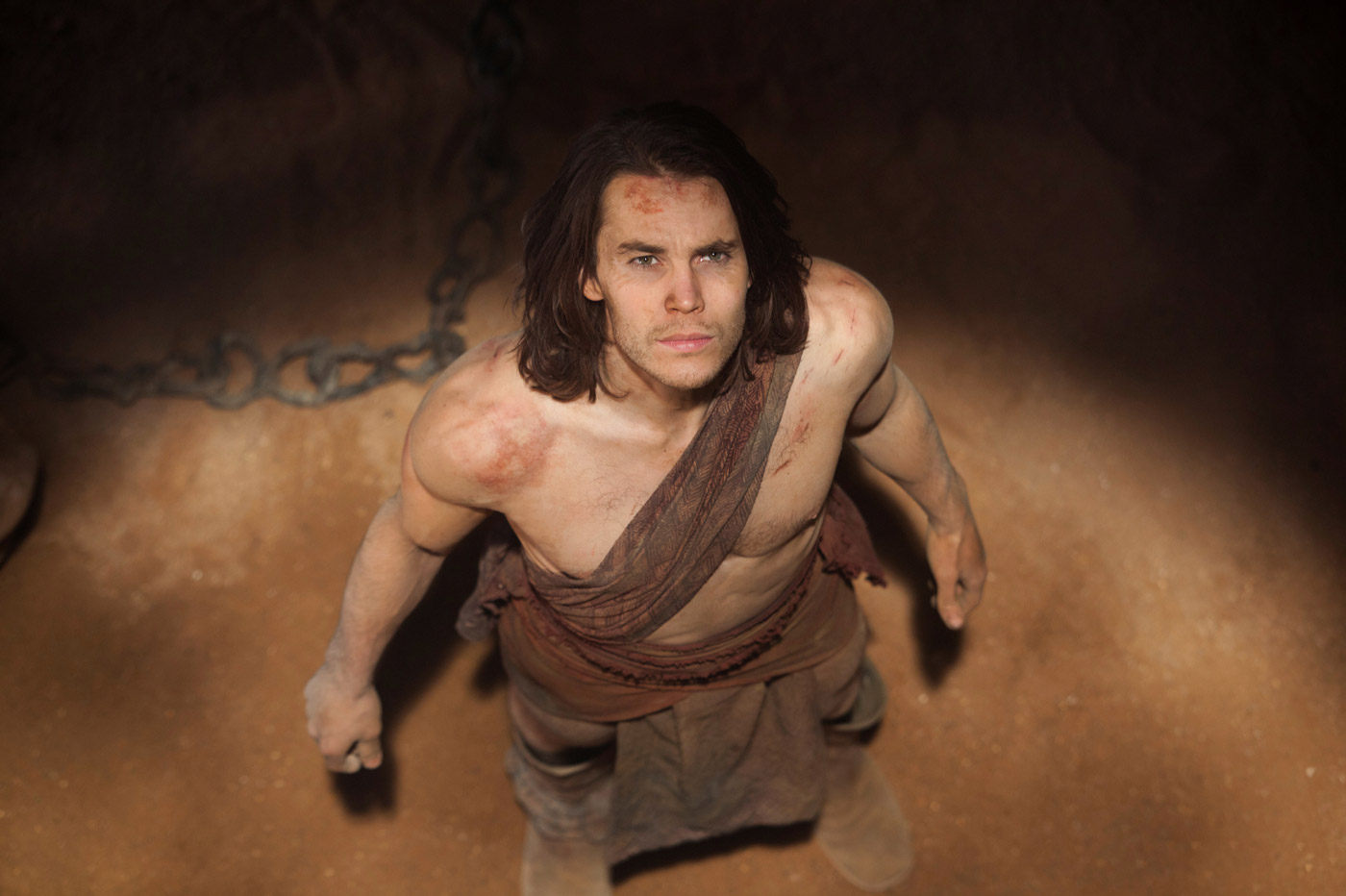

After a long, convoluted and contentious back-story, John Carter, named for a character created by Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs in the early 1900s, will finally hit movie screens this year. Carter is a Civil War vet who finds himself on the planet Mars and becomes embroiled in a war between several races of fantastical creatures. Comic book lovers point to Carter’s amazing leaping abilities – due to Mars’ weaker gravity – as the antecedent of uncanny powers attributed to later superheroes.

According to legend, a movie version was begun in 1931. This edition would have had a claim to be the first animated feature, had it come to fruition. Stop-motion wizard Ray Harryhausen, in the 1950s, and John McTiernen in the 1980s both pondered films. In 2004, Robert Rodriguez was attached to direct A Princess of Mars, the best known of Burroughs’ Carter books. Kerry Conran (Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow) and Jon Favreau (Iron Man) were also onboard at various points.

But John Carter, as the film is now titled, may be best known by film buffs of the future as the first live-action effort from writer-director Andrew Stanton, best known for his CGI animated features for Pixar, Finding Nemo and Wall-E. While Pixar itself is not directly involved in John Carter, Disney, its longtime distributor and current owner, is releasing the film. The Pixar process, which has famously led to 12 straight hits, involves detailed pre-visualization and animatics edited, critiqued and “plussed” dozens of times before the movie ever begins.

After two decades of success in animation, Stanton declared himself “spontaneity-starved,” and took on John Carter. He brought over Pixar’s collaborative approach, which values “making mistakes early” and constant improvement throughout the project.

Cinematographer Dan Mindel, ASC, BSC was fascinated to see the two mind-sets blend to reach a common goal. “Disney has had to adjust to absorb Pixar,” says Mindel. “They’ve realized that they must learn to work in a much more compact, efficient way. It’s amazing how forward-thinking and liberated the Pixar people are compared to the studio conglomerates. I loved being in the same space because the way they think is so refreshing – they learn something from each project and apply it on the next one.”

Second unit director of photography Bruce McCleery agrees, adding that “Andrew and his Pixar team are brilliant storytellers, but they are also brilliant at culling contributions from creative collaborators. Their methodology is inclusive and fun. Working with them was a completely unique experience.”

Despite the high-profile 3D release of John Carter and the complex file-based workflow and post process, Mindel is a true believer in 35-mm anamorphic capture. “I try very hard to persuade whomever I’m working with to allow me to shoot on film, and to shoot anamorphically,” he states. “It’s the most pure, high-definition way of capturing a scene, short of Showscan or IMAX. I realize there are so many different ways of making movies. But I wanted to focus on just one way, and really learn how to do it inside and out.”

Mindel says the wide field of view in anamorphic feels human and natural. He treasures the imperfections and aberrations he finds in older, hand-cut Panavision anamorphic lenses. “At a purely organic level, the light does unmanageable things when it hits an aberration. An unquantifiable magic happens, and I love that!”

He felt strongly that those aberrations, along with the texture and grain that film brings, was essential to John Carter. “I wanted to deliver images that felt inherently realistic in spite of the fantastical creatures and the extensive digital-visual-effects technology behind them,” he adds, employing Panavision Primo and C-series anamorphic lenses, and AWZ and ATZ Panavision zoom lenses throughout, along with Kodak Vision3 500T Color Negative Film 5219 and 200T 5213 film stocks.

A blended workflow permeated John Carter. Huge-scale stage sets built in the U.K. were coupled with exterior footage shot in the red rock canyons and deserts of Utah. Traditional Hollywood-style live-action production techniques were melded with the Pixar culture and approach. While the filmmakers had to consider their options for the end game – a 3D release – early on, Stanton ultimately felt shooting native 3D would be too much of a hindrance. A screening by Disney of Alice of Wonderland, a film that carefully mapped out 3D space on the set in preparing for a post conversion, only made it clear that “those processes would be outdated by the time John Carter was ready to convert,” Mindel reflects. “So we just went forward and shot the way we normally would have, without making any concessions or adjustments for 3D, which was a huge relief.”

Proof-of-process tests began around February 2009, a year before the release of Avatar validated a new generation of motion capture and other technologies. John Carter would require pioneering motion capture techniques, extensive pre-visualization, and massive blue- and green-screen sets to tell the story. Live action and CGI character interactions are more physically intimate and extensive than in Avatar.

Visual effects supervisor Peter Chiang, VES, with Double Negative in London, created a production bible that showed how each character should be composed and framed. Chiang and his team also made short videos explaining how to get various characters into shots. Often, human actors were in the shot whose movements were being captured for eventual application to CG creatures. These human actors wore motion capture suits and stood on rostrums, stilts, boxes and platforms to mimic the stature and movements of 12-foot-tall, four-armed, tusked Martians. Their characters would eventually fight with, carry and otherwise interact with the human cast.

“These guidelines helped us understand the spatial relationships between a human and a creature that wouldn’t be put into the scene until later,” McCleery observes. “Working that out was much more complex than it sounds.”

Many decisions were hammered out during the extensive preparation period. Stanton worked closely with Halon Entertainment, a pre-visualization company with experience on many VFX blockbusters, including Star Wars: Episodes II and III, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, and War of the Worlds. Halon uses Autodesk Maya and MotionBuilder on Macs, sometimes with Windows 7 running on Mac hardware. Dan Gregoire served as Halon’s pre-vis supervisor. He, along with a team of four, was on the project for a year.

“Andrew’s background in animation meant that John Carter had a well-blocked-out storyboard layout,” says Gregoire. “That gave us a very solid foundation on which to base our pre-vis. Once we started looking at the sequences in an editorial fashion, Andrew used our pre-vis tools to ‘plus’ everything – to riff off of and change ideas, to get into sets and see how the dimensions of certain sets were affected by certain lenses, and by the scale, proximity and motion of the characters. It became a much more free-form, creative environment in which he could build upon his earlier efforts.”

As with every other aspect of the shoot, Halon had to take its game up a notch. “John Carter was the first time we deployed our full virtual camera system,” Gregoire adds. “The ‘White Ape’ sequence that you see in the trailer was approached differently than the other seven sequences that we worked with. We actually put second unit director Mark Andrews in an Xsens MVN suit, which is an inertial motion capture system. We had Mark act out all the actions of the white apes throughout the sequence. We took that into MotionBuilder, cleaned it up, and compiled it into scenes. Then we used our motion capture volume and a virtual camera to shoot them, rather than having an artist animate a camera.”

Combined with rough characters, these pre-vis scenes were edited together. Stanton experimented with the elements, and a year or more later, used the results to show Mindel, the actors and his other collaborators what he had in mind. The virtual camera volume was also used as a way for Stanton to “scout” digital sets. Gregoire would put the digital sets into the environment, and place Stanton inside the set, giving him a much better idea of how to use the sets effectively than he could get from looking at a monitor.

“Andrew used the pre-vis like he might use storyboards in the animation process,” says Gregoire. “He used it as a playground to figure out what would work. When he discovered something wasn’t working, he would come in and completely redesign it. Pre-vis allows you to have fun in a safe, creative environment where making the wrong choice isn’t the end of the world. It allows you to make mistakes, discover them early and correct them.”

Chiang had to adapt his methods to work with the idiosyncrasies of anamorphic treasured by Mindel. He and his team mapped out each anamorphic lens, and mounted encoders on lenses to track and record how focus changed during each shot. Mindel says that Chiang’s early career experience in pre-digital-era visual effects was especially valuable in his work today.

“Our overall challenge on John Carter was to design shoot methodologies that would enable us to create photo-real creatures and environments,” says Chiang. “We had to redesign our creature pipeline to create more sophisticated and convincing characters.

“We shot grids for all the lenses so that we could de-lens the scanned images and add the visual effects,” he continues. “Dan and Andrew wanted the anamorphic format to enhance the cinematic experience. This look needed to be emulated in everything we generated and composited and served as a guide, telling us whether we had been successful in generating convincing images. If it didn’t fit in with the original photography, it would fail as a shot.”

Chiang’s main concerns on the set were the eyelines for the humans and the facial motion capture for the actors portraying the Tharks, a race of green Martian warriors with whom Carter interacts. These actors wore tracking dots on their faces and were fitted with headsets that held two cameras that recorded their performances. This data served as a starting point for the facial animation of the Thark that would replace the human actor but retain his or her movements. A clean plate with only the human actors was always photographed as well to reduce the need for cleanup later. Then a low-resolution Thark was animated into the scene and shown to Stanton for approval. Once approved, the Thark was then “lit” and rendered at higher resolution. Once this step met with approval, the costume, muscles and effects elements were generated based on that animation. Compositing was a final step in this process.

“The mixture of art and technology made this a dream project,” says Chiang. “Everyone worked in tune to make everything the best it could be.”

Mindel says that working with Chiang and his team required a lot of give and take. “With my background, I want to capture all the texture and contrast – the dust and the smoke and the backlight – in camera,” he explains. “But Peter would come to me and say, ‘Tone it down a bit, and we’ll fix it for you later. We need to be able to capture the image in a certain way.’ One has to have a strong element of trust, because at a certain point, your images are in their hands. It’s a very hard thing to do, to hand over control to another person. But on the other hand, if you don’t, the cost of repairing the work later is enormous. One has to appreciate how difficult it is for the visual effect people. If you can help them, it makes all of us look much better in the end.”

The first four months of production took place in London, mostly on sets designed by Nathan Crowley and built at Shepperton and at Longcross, where some massive warehouses have been converted to film production facilities. The filmmakers were limited in how much they could reveal about the sets, but adjectives like “humungous” and “astonishing” were common.

Long before production began, Mindel was communicating with his rigging gaffer and lighting team to design the lighting scheme. Their extensive plans were shared with the visual effects team, which also took the step of gathering LIDAR information in every set. LIDAR uses laser pulses to map environments.

One of the biggest set-pieces was an air battle between three different ships requiring a good deal of old-fashioned lighting work. Massive ships, about 110 feet long, were mounted on gimbals and surrounded by green screen. In the story, these ships rely on sunlight, so they block each other’s sunlight as a way of disabling each other. Meanwhile, evil creatures that give off a weird blue light attack. Another lighting effect was associated with a vaporization weapon.

“There are lot of CG elements, but they are suggested with interactive lighting on the set,” says McCleery. “There were hundreds of moving lights, changing light values and huge shadows. We’d be on a wide lens, doing a 180-degree shot, swinging around on a Technocrane at full extension that was mounted on a 20-foot scaffold.”

The sequence included hundreds of Spacelights, at least 15 Dinos, flashing lights and a crane mounted with soft sources and green screens that could be dropped in close to bring sky ambience.

In the Utah desert in May and June of 2011, the production was assaulted by wind and sandstorms. Goggles and burnooses were standard apparel. Mindel fought hard for as much of the shoot to be done in these real conditions as possible, even if the filmmakers may have gotten more than they bargained for with the weather. “All the uncontrollable natural phenomena did give the film a visceral, unpredictable quality, and contributed to its unique, idiosyncratic texture,” concludes McCleery.

Principal photography was finished during a month-long reshoot session at Playa Vista in Los Angeles. Lab services were provided by Technicolor in London and Fotokem in L.A., and the DI was done at Company 3 in Santa Monica.

Mindel feels that his most important contribution to films of John Carter’s ilk is to simply maintain a sense of reality through the careful introduction of imperfection. He frets that big-time filmmaking has become too focused on the technical, at the expense of storytelling.

“Once people are engaged and invested, they just want to see the story,” Mindel states. “John Carter was an amazingly technological undertaking. We tried very hard to keep the Luddite attitude out, while keeping a handmade feeling in.”

By David Huering / photos by © Disney / John Carter™ ERB, Inc. / Frank Connor